We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Occasionally, the most satisfying cinematic experiences come from really letting a movie sink into your skin and live with you, giving yourself over to a movie that deliberately takes the time to stretch its legs and ruminate on elements that may get brushed over more quickly in a more traditional film. Indeed, so many of the most critically acclaimed movies ever made could be categorized as “slow-burn” films, movies that ask for your patience and reward you with depth and detail.

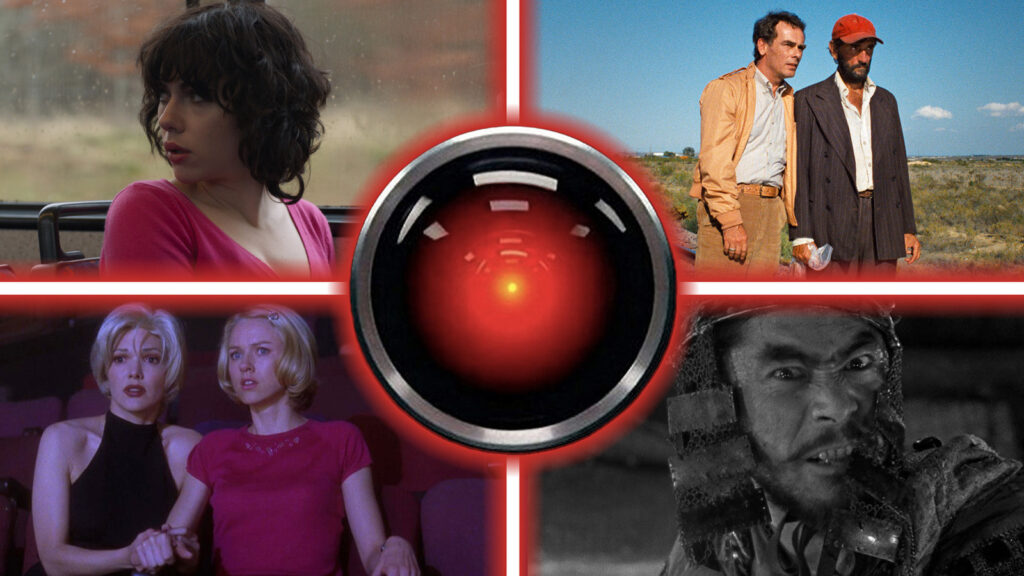

The great thing about the “slow-burn” label is that it encompasses an endlessly diverse selection of film genres. Many may think of purely arty character dramas when faced with the idea of a slow-burn movie, but some of the best movies of all genres fit the bill: sci-fi, horror, westerns, action — all is fair game. They all share an identical strength when pulled off correctly: digging deep into the bones of their world and their characters, and allowing the audience to ruminate and appreciate the artistic processes of filmmaking in a new way.

Here are 12 of the best slow-burn movies of all time, ranked.

12. Resurrection

We’re giving space in the initial entry on this list to call out one of the best movies of 2025 (though it didn’t really start making rounds properly until early 2026). Chinese filmmaking elegist Bi Gan had already proven himself a master of the contemplative slow-cinema style with his films “Kaili Blues” and the 3D-released “Long Day’s Journey Into Night.” He continues his reliable style of poetic cerebration with “Resurrection,” an anthology epic that asks the viewer to sink in and feel the varying textures that Bi has so mesmerizingly captured with his images.

With “Resurrection,” Bi stitches together a surrealist odyssey that engages in and reveres different modes of storytelling, types of filmmaking, and genres, weaving together elements of whimsy, violence, and tragedy that communicate the history of Chinese cinema and of the medium at large. We’re treated to an assortment of stories led by actor Jackson Yee, all relating to one of the six human senses as understood by Buddhist beliefs, highlighting elements of the human experience often not tapped by filmmaking.

It all culminates in Bi’s filmmaking specialty: a 30-minute unbroken long-take sequence tracking the hyper-stylized romantic tragedy of a New Year’s Eve night in 1999, as two young lovers navigate a threatening world beset by criminality, bathed in vivid red lighting and bathed in a master’s sense of cinematic emotion. With “Resurrection,” Bi retains his status as one of our most deeply felt filmmakers working today.

11. Burning

The first film from South Korean director Lee Chang-dong after an eight-year gap, and the last for the following eight years at least, “Burning” is the perfect example of how a “slow burn” feature has the capability to sink into your skin by deliberately drawing out more conventional cinematic instincts into something more troubling and abstract. The tension of the central character dynamic of “Burning” is the crux of the film, but it’s the ambiguity between the three lead performers that makes the film so intoxicating. Even after the film’s final images, you may not be sure about who your sympathies should align with.

That may sound frustrating, but it makes for an intoxicating viewing experience. Based on “Barn Burning” from author Haruki Murakami’s short story collection “The Elephant Vanishes,” Lee complicates and obscures what you think you know about these characters, and subtly alters the source of the film’s anxieties as it goes along. This wouldn’t be possible without the three rock-solid performances at the film’s center from Yoo Ah-in, Jun Jong-seo, and especially Steven Yeun, who takes on a cryptic, enigmatic, dangerous temperament here that serves as his career’s defining performance, topping our ranked list of Steven Yeun movies and TV shows.

“Burning” asks a lot of its audience: patience, trust, and a willingness to sit with the unknown. It doesn’t hold your hand and is measured and deliberate in getting to its final images. But it’s a movie bound to stay with you if you give it your attention.

10. First Cow

Not all slow-burn films are three-hour sagas that ask you to sit with desolate uncertainty and enigmas. Take “First Cow,” writer-director Kelly Reichardt’s 19th-century American drama about an unlikely pair of friends navigating the wild unknown of the Pacific Northwest and embarking on a new business venture: selling delicious homemade biscuits made from the milk of the only cow in the territory, belonging to a moneyed British landowner.

Though “First Cow” moves at Reichardt’s typically unhurried pace and is made up of long passages of silence and some ambiguous gestures that could leave some audiences cold, at its heart, it’s a film about friendship and the harsh mechanisms of capitalism that this new land was already being defined by. These dynamics crush even the most enterprising dreamers trying to make a living for themselves, making “First Cow” a bittersweet fable that rewrites the rules of the American Western to tell the story of America in a brand-new way.

“First Cow” subtly infuses a somber sense of fatalism into the wholesome friendship at its center, acutely aware that most roads along the path of the American Dream are paved with precariousness and menace. But there’s a loving story shared between its characters that finds personal solace amidst unforgiving, unabated diffusion of industrial progress.

9. Persona

Arguably, Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s most revered and influential movie, “Persona” rewards your patience and your willingness for close examination. Often cited as one of the most psychologically complex and rich films ever made, it fits hundreds of research papers worth of ideas into its modest 84-minute runtime. “Persona” is a slow burn, but it’s also streamlined in its delivery of thematic intricacies.

Led by regular Bergman collaborators Bibi Anderson and Liv Ullmann, the film follows Anderson as the nurse Alma, who retreats to a remote cottage to better care for her new patient, famed stage actress Elisabet Vogler (Ullmann), who has suddenly gone mute. Once there, the dividing boundaries between each woman’s sense of self begin to deteriorate, and an ominous psychodrama of self-investigation and projection ensues.

The heady ideas that embody “Persona,” investigating the politics of the self and the delicate nature of identity, have served as fertile ground for endless intellectual discussion and as inspiration for future filmmakers who made a name for themselves in the realm of surreal, dreamlike narratives. “Persona” endures because it gives the audience the power to conduct their own internal investigations and draw independent conclusions about the film’s central characters. It’s one of the most outstanding examples of art that engages the audience through poetic mystery.

8. Under the Skin

Jonathan Glazer’s 2013 feature “Under The Skin” is a sci-fi film that pays tribute to its meticulous, exacting forebears like “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “Solaris.” Based on the 2000 novel of the same name by Michael Faber, it stars Scarlett Johansson as a stoic, merciless alien lifeform that has taken the shape of a human woman, and takes to the dark, rainy streets of Scotland to trap and harvest the unwitting men who cross her path.

“Under the Skin” is a uniquely unsettling movie, with Glazer using a slow, deliberate pace to craft sequences of ominous tension and haunting, surrealistic imagery. The film carries a droning tone of impending dread, as Johansson blithely, impassively prowls the city streets for her next victim, with Glazer capturing footage Guerrilla-style, often filming people who don’t know they’re in a movie. The story intersects modes of examining the human condition: how so many of the men this being picks up find themselves in this situation because of their objectification of the human body, and, simultaneously, how Johansson’s casual barbarity denies any notion of human empathy.

The film becomes no less distressing as it moves towards its inevitable climax, but it does open its heart as the story turns towards the ideas of understanding and mercy. It is one of the most upsetting yet beautiful sci-fi films of the 21st century, all the better for how rigorously it composes its story of alienation and disconnection.

7. Stalker

Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky is notorious for his inscrutable, deliberately paced stories, which investigate the human condition through enigmatic, opaque genre lenses. Such is the case with “Stalker,” a sci-fi story personified by the careful contemplation through which it renders its story beats, seeking to lull the audience into a state of enthralled meditation, and we follow the journey of the characters.

Loosely based on the 1972 novel “Roadside Picnic” by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, “Stalker” follows the journey of a writer and a professor who are guided by a man known as the Stalker through a restricted area of land affected by supernatural phenomena, known as The Zone, where they expect to find a room that grants one’s greatest desire. The journey, naturally, becomes one of great psychological introspection, as the men’s surreal quest culminates in a pronounced internal reckoning.

“Stalker” is one of the most influential sci-fi films of all time, and it’s another movie in which audiences reap tremendous benefits from giving themselves over to its slow rhythms and cadences. Tarkovsky asks you to luxuriate in all of the strange textures of his film with an open-mindedness. He’s not guiding you by the hand through The Zone, or the details of the world of “Stalker,” but he trusts you’ll find your own understanding all the same.

6. Paris, Texas

One day, German filmmaker Wim Wenders got to thinking that, there probably wouldn’t be much of anything better than watching famed character actor Harry Dean Stanton silently and mournfully wandering through painterly images of the Texas desert in search of his estranged son and wife. Turns out he was right, which is why “Paris, Texas” has only increased its critical cache over the years, and appears at number 4 on our list of the 10 best movies set in Texas.

Like many of the other slow burn movies on this list, Wenders does an expert job of entrancing you through a soothing pace, which supports a meditative, melancholic story about America, family, loneliness, and self-discovery. Stanton is such a world-class actor that you can map a million tiny different emotional frequencies onto the unique contours of his unforgettable face—he moves you with a simple stray look.

The film’s famous scene between Stanton’s character Travis and his wife Jane (Nastassja Kinski) has rightfully gone down as a pivotal sequence in American moviemaking, yielding a type of emotional closure that still leaves you with a few tragic dangling threads to mull over as you continue to turn small moments of the film over in your mind. It’s not a question that you will be doing so, as “Paris, Texas” is a film that’s hard to keep from lingering.

5. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Modern master of the contemplative genre aptly known as “slow cinema,” Apichatpong Weerasethakul made history as the first Thai filmmaker to win the Cannes Palme d’Or with this peculiar, mystifying drama. It’s so fully enmeshed in specific ideas of Thai culture and folklore that it can appear impenetrable to those approaching from the outside, but its uncanny textures are what make it such a singular viewing experience.

The film follows a man named Uncle Boonmee (Thanapat Saisaymar) who retreats to a house in the woods to be cared for by his sister-in-law and nephew as he wrestles with a failing kidney. While there, the group has encounters with spirits from beyond: the ghost of Boonmee’s wife and that of his son, who appears as a red-eyed monkey, speak to the family. The film quietly wrestles with the inherent ideas of death and transformation as characters stilly speak to one another, with the film occasionally taking time to break off for a new digression, like a flashback hundreds of years earlier to a Thai princess having a strange encounter in the woods.

Weerasethakul isn’t overly concerned with explaining his situations or images, trusting that his film speaks for itself emotionally and spiritually. Touching on elements of specific cultural history, like Thailand’s violent experiences with communists, “Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives” is a meditative feast that fluidly examines a metaphysical reality in which we’re connected to one another and to our own pasts.

4. Seven Samurai

You could throw a rock, and you’d probably hit a movie that was influenced by “Seven Samurai.” Legendary Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa’s three-hour epic about a group of swordsmen who take up the task of defending a helpless village against an outside attack establishes the template for so many genre films that would expand on its core ideas and become phenomena themselves. Indeed, it should be no surprise that George Lucas cites “Seven Samurai” as his favorite film of all time, with the way that its plot structure and imagery, along with a selection of other Kurosawa films, would go on to influence “Star Wars.”

In terms of its slow-burn status, “Seven Samurai” may take its time getting to its climactic showdown, but it is never less than wholly engaging as it assembles its players and sees them preparing for their mission. Kurosawa and cinematographer Asakazu Nakai capture some of the most beautiful and harrowing black-and-white photography ever seen on film, and the performers, led by the legendary Toshirō Mifune, fully inhabit this scenario of grand heroism and conflict.

Despite molding itself around a monumental final battle, “Seven Samurai” is primarily concerned with the cyclical inevitability of violence, and utilizes its long runtime to highlight somber moments of horror and confusion amid a world of battle. Kurosawa films action like no one else, but he also undercuts with an inexorable sort of sorrow at watching the people sharing a world, tearing themselves apart.

3. Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

The final boss of all slow burn films, “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles,” from French director Chantal Akerman, asks the viewer to live practically in real-time with the titular character, played by Delphine Seyrig, as she moves through the motions of her domestic routine, involving her regular chores and the sex work that she makes a living from. At over 200 minutes long, “Jeanne Dielman” is a radical exercise in an experimental form that supports a progressive story about the restrictions of patriarchal normality. It’s one of the best films of all time, as seen by the fact that “Jeanne Dielman” was most recently selected on Sight and Sound’s list of greatest movies.

The selection wasn’t made without controversy from those who fail to pick up the urgency within “Jeanne Dielman’s” deliberately monotonous frames. But it’s in that calculated sense of appraisal of an audience’s patience that the film finds its remarkable cinematic captivation. Akerman lulls you into the hypnotic rhythms of Jeanne’s day-to-day with a formal method of mesmeric repetition that the film becomes its own type of meditation, which makes it all the more crushing when Jeanne’s life eventually faces a substantial shift.

It’s a little hard to recommend a movie that is essentially a lady doing chores for 3 hours, but it’s the exact kind of testing of the boundaries of cinema that makes the art form so exciting. If you fall under its spell, you may be surprised by the degree to which “Jeanne Dielman” refuses to let you go.

2. Mulholland Drive

Earlier, we spoke about Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona” and the influence its story of the haunted, confused sense of identity between the two women at its center had on future psychological dramas. Look no further than “Mulholland Drive” to find what is essentially the 21st-century update for that very premise. Directed by the one and only David Lynch, “Mulholland Drive” transposes its two-hander psychodrama onto contemporary Los Angeles, where the bond between an aspiring actress and an established star becomes an enigmatic vista of dreams.

It’s a film ripe for endless debate and discussion, from the various, layered meanings of its puzzling thematic imagery to explainers about the film’s perplexing timeline that guides “Mulholland Drive’s” story. Lynch is a director famously evasive of simple answers in his movies, devoted to the idea that many of the ineffable types of emotions he’s reaching towards aren’t easily explainable in language—if you were to ask him, it’s why cinema exists.

In a filmography full of masterpieces, “Mulholland Drive” may just be Lynch’s defining feature, the culmination of all his recurring notions of surreality, horror, noir, and empathy, which are given extraordinary life by Naomi Watts and Laura Harring. There has never been, and never will be, an imagemaker and storyteller who can properly reproduce what Lynch has contributed to cinema, and this is his finest hour.

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick’s legendary sci-fi adventure “2001: A Space Odyssey” is one of the most innovative, influential movies ever made. True to form for the tenacious, meticulous director, it’s also one of the most satisfying slow burn experiences ever assembled, gradually guiding audiences first through a vision of the past, then a vision of the future, in which mankind is beset with a troubling inevitability of the future.

Despite its ambiguous narrative trajectory and meaning, “2001: A Space Odyssey” proves that Kubrick is still a crowd-pleasing director where it counts. His vision of the dull, humdrum reality of future spaceship living is knowingly tongue-in-cheek, and the back half focus on the ominous HAL 9000 sees him crafting one of the great movie villains. For the reputation “2001: A Space Odyssey” has earned for being cryptic, it remains a crowd-pleaser for its tight balance between the recognizable and the obscure, packaged in a wondrous cinematic spectacle.

That’s an idea taken all the way to the climax, as astronaut David Bowman (Keir Dullea) is pulled through an interstellar vortex in the film’s final sequence, visualized as a hallucinogenic, unearthly barreling of light and sound, leading to an otherworldly conclusion. If we’re talking slow burn movies, it’s hard to place another that has the same satisfaction and impact as “2001: A Space Odyssey,” which is why it has retained its potency after all these years.