It’s hard to find a science fiction fan who doesn’t have a soft spot for steampunk. Generally understood as a subgenre focused on the steam-powered machinery prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th century and its hypothetical developments, the realm of steampunk is open to lots of variation and definitional debate. It includes works of hard, historically thorough sci-fi, as well as pure fantasy where the bells and whistles of early industrialization come into play as a freely-defined aesthetic. Anything sci-fi with that vintage-advanced feel, that emphasis on old-new tension expressed through dense industrial landscapes made out of brass and clock movements, can fall under this particular rusted umbrella.

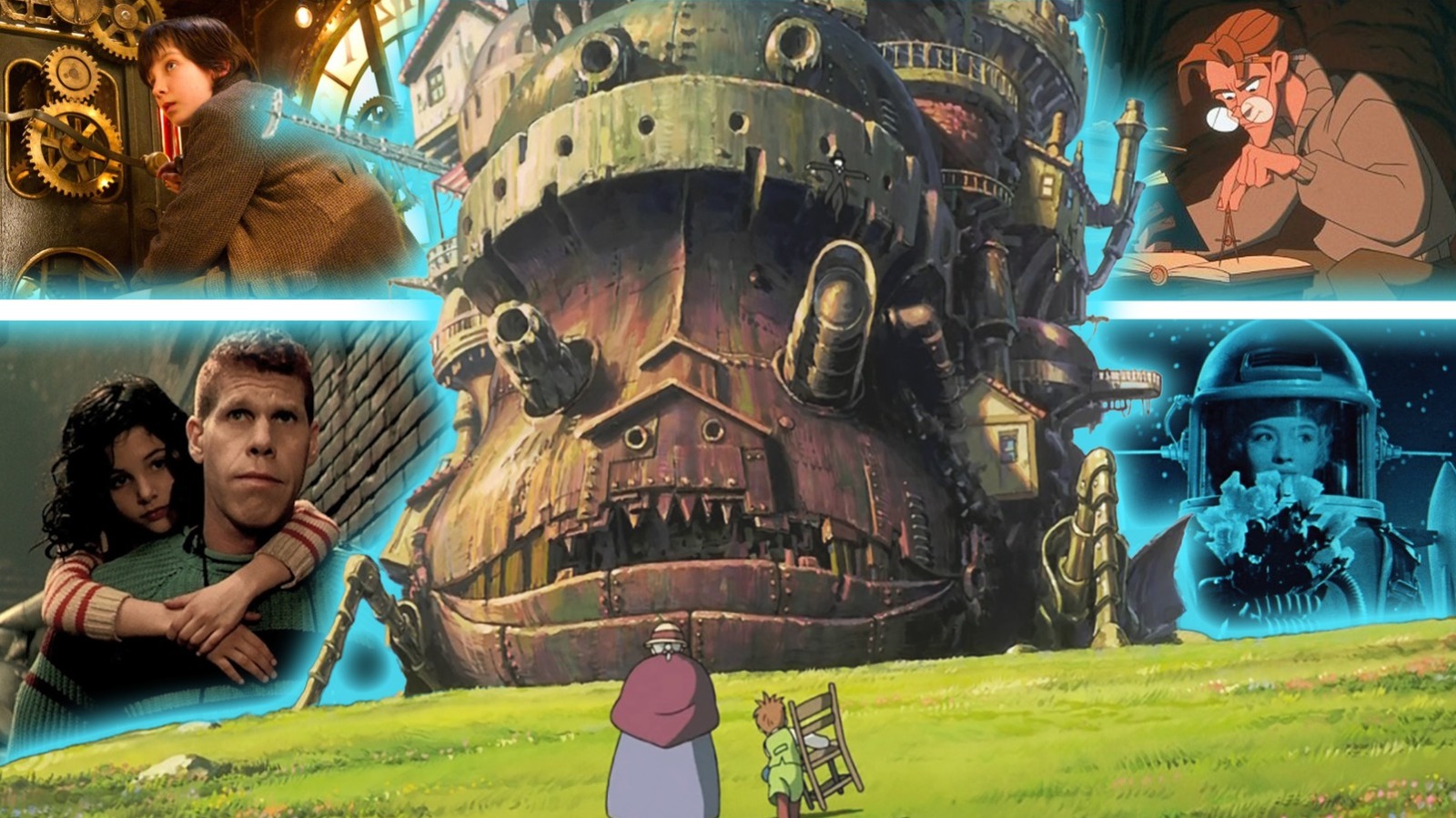

Movies themselves, those once-thought-impossible illusions born from 1890s machines, are one of the most steampunk of inventions — so it’s only appropriate that cinema should have a rich tradition of films that borrow from the genre to build out their worlds. Here, we have ranked the best steampunk movies of all time, and you will find that a third of the list is made up of Jules Verne adaptations, a third of it is made up of animation, and a third of it is Czech. Put on your top-hat-and-goggles combo, and dive in.

12. Back to the Future Part III

In “Back to the Future Part III,” we pick up immediately after the “Part II” cliffhanger that left Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) stranded in 1955 yet again, while the 1985 version of Emmett “Doc” Brown (Christopher Lloyd) got zapped to the year 1885. With help from the 1955 Doc, Marty dusts off the DeLorean and travels into the past, where he and the 1985 Doc get caught up in a Western adventure. And then there’s the kicker: Because the DeLorean’s fuel line got damaged during the trip, they’re forced to make do with late-19th-century technology and still somehow find a way back to their home year.

Could it be the best “Back to the Future” movie? In place of the labyrinthine, flowchart-requiring temporal bustle of “Part II,” “Back to the Future Part III” offers a pared-down fish-out-of-water story about Marty and Doc fending for themselves in the Old West — a setup that opens up myriad golden opportunities for comedy and pathos. Both director Robert Zemeckis and screenwriter Bob Gale relish the opportunity to affectionately rib Western tropes, which make for a surprisingly apposite pairing with the franchise’s sci-fi slant. On top of all that, “Back to the Future Part III” also becomes a sneakily great steampunk film in its back half, as Doc makes eye-popping technological miracles out of steam-powered machines.

11. April and the Extraordinary World

Few movies incorporate the aesthetic of steampunk with as much commitment as “April and the Extraordinary World,” one of the best non-Hollywood animated movies of the 2010s. Based on the works of French comic artist Jacques Tardi, the feature debut of Christian Desmares and Frank Ekinci proposes an elaborate alt-history world in which Napoleon III was killed in an explosion caused by a dangerous scientific experiment, the Franco-Prussian war never happened, and France has arrived to the year 1941 under the rule of Emperor Napoleon V. In this alternate reality, the world’s scientists routinely go missing under mysterious circumstances. As a result, technology has remained stuck in the steam age, and Paris is now a gritty steel metropolis with airship buses, crisscrossing ropeways, and two Eiffel Towers.

After establishing this stunningly gorgeous world of grays and reds, the movie proceeds to play out a complex, multi-layered sci-fi saga within it. April Franklin (Marion Cotillard) is the daughter of two scientists who continued the life-extending experiments started all the way back in Napoleoen III’s time and seemingly died for it during an escape from government agents when April was a child. Years later, while continuing her parents’ experiments, April discovers evidence that they may still be alive — sending her on a search that tunnels into the dark, perilous underbelly of this retrofuturist Paris just as much as any steampunk fan could hope for.

10. Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows

Guy Ritchie’s “Sherlock Holmes” films are great, actually. 2009’s “Sherlock Holmes,” for one, is a surprisingly fun and spirited yarn. Its sequel, 2011’s “Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows,” is even better. Working with an increased budget and faced with the expectation to go bigger for the second round, Ritchie opts to have fun with the very idea of a gun-toting, day-saving action hero Holmes: The industrial, implicitly violent landscape of late-20th-century Europe gets reduced ad absurdum down to a series of organized cause-effect relations between machines and operators, until it functions as a chessboard where moves can be foreseen.

It’s in this context that “A Game of Shadows” casts Robert Downey Jr.’s Sherlock as both player and commentator, willing the action blockbuster into being by deconstructing and reconstructing its formula. Caught in a battle of wits with Professor James Moriarty (Jared Harris), who’s merrily moving pieces into place for a world war that will benefit him, Holmes embarks on a run-through of genre tropes that he’s able to anticipate and shift around — thereby turning all action into a matter of intellect. It’s a thrilling homage-slash-subversion of genre formula, and Ritchie’s interest in steampunk markers is integral to it. Every explosion, every click of every gun, and every other technological extravagance becomes another shift of gears in the great contraption that is the world in Holmes and Moriarty’s eyes.

9. Hugo

Martin Scorsese has tried his hand at many different genres, but “Hugo,” his 2011 incursion into kid-friendly adventure cinema, is something special. Adapted by screenwriter John Logan from the illustrated novel “The Invention of Hugo Cabret” by Brian Selznick, Scorsese’s most awarded film ever at the Oscars (tied with “The Aviator”) follows Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield), an orphan boy living in the walls of a train station in 1930s Paris.

Hugo is determined to repair an automaton left behind by his clockmaker father (Jude Law), using notes that his father put down in a notebook. One day, he is caught stealing parts by surly toy store owner Georges (Ben Kingsley), and when George takes away Hugo’s notebook as punishment, he agrees to work at the store as compensation. Soon, Hugo strikes a friendship with Georges’ goddaughter Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz) and learns that Georges is in fact legendary 1900s filmmaker Georges Méliès, thus opening up a greater mystery that may connect the shop, the automaton, and the early days of cinema.

Scorsese shoots all of this intrigue as a rambunctious blockbuster, complete with James Cameron’s favorite use of 3D in a movie, and the retro-sci-fi elements of Hugo’s investigation are all steampunk to the hilt. The whole movie feels like a diorama in the best way, as though you could reach out and touch the train station’s intricate metal structures with your hands.

8. Invention for Destruction

Czech filmmaker Karel Zeman was a pioneer of lavish, artisanal special effects who catapulted sci-fi cinema about a half-century forward with his ambitious midcentury productions blending live-action and animation techniques. Two of the films on this list are his, including this one: 1958’s “Invention for Destruction,” one of the best movies based on Jules Verne books (in this case, 1896’s “Facing the Flag” along with assorted others).

Originally released in the U.S. in 1961 with an English dub and the title “The Fabulous World of Jules Verne,” this massively successful and influential film tells of the conflict between a scientist (Lubor Tokoš) and an evil count (Miroslav Holub) eager to build a super-bomb. Being that Verne himself was an influential pioneer whose work directly influenced steampunk as an aesthetic, the alignment of his sensibilities with Zeman’s could only yield something major, and surely enough, “Invention for Destruction” visualizes Verne’s meticulous visions more faithfully and dashingly than virtually any other film adaptation in history.

The key to it all is in Zeman’s incorporation of animation and painted-on effects, with which he pushes every element in the film’s metal-plated mise-en-scène to extremes of plastic richness. Through this embrace of retrofuturistic Victorian maximalism, “Invention for Destruction” puts on an unparalleled display of showmanship, while displaying an acute understanding of Victorian-era futurology — whereby industrial technology could be both magic and menace.

7. Atlantis: The Lost Empire

There is no other Disney flick quite like “Atlantis: The Lost Empire,” a Michael J. Fox sci-fi movie that deserves way more love. Expressly conceived by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise as a departure following the more conventional Renaissance pomp of “The Hunchback of Notre Dame,” this financially underwhelming but artistically bracing 2001 effort had the gumption to use Disney’s turn-of-the-century resources and creative openness to do steampunk like it had never been done before.

Eager to evoke the spirit of Jules Verne through the capabilities of big-budget animation while also paying homage to the oeuvre of comic artist Mike Mignola (who also acts as the film’s production designer), “Atlantis” brings to life an aesthetic that still feels startlingly futuristic 25 years later, even though the story being told takes place in the 1910s. In fact, no other movie could have made a more appropriate record-breaker for most extensive use of CGI in a cel-animated Disney feature; the film’s whirring machines and majestic watercraft are all the more stunning for being rendered in language-breaking 3D.

The plot, in which linguist Milo Thatch (Fox) and his expedition crewmates get caught between their reverence for Atlantis’ indigenous culture and the capitalist voracity of their superiors, is relatively simple. But that scarcely matters when “Atlantis” carries it out with such cinematic gusto on all fronts — and with such an irresistibly charismatic supporting cast in tow.

6. The Mysterious Castle in the Carpathians

Another great Czech adaptation of Jules Verne is 1981’s “The Mysterious Castle in the Carpathians,” helmed by notorious comedy director Oldřich Lipský. Adapted from the 1892 novel “The Carpathian Castle,” sometimes grouped as a minor work in Verne’s oeuvre yet notable for having potentially influenced Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” the film retrofits the eerie Gothic tone of the source material into playful, eccentric, Terry Gilliam-esque comedy.

More narratively to-the-point than the novel, Lipský’s film centers Count Teleke of Tölökö (Michal Dočolomanský), an opera singer reeling from the mysterious death of his stage partner Salsa Verde (Evelyna Steimarová). One day, while traveling through the Carpathian mountains with his servant (Augustín Kubáň), the count meets forester Vilja Dézi (Jan Hartl), and the two men reach the castle of a dangerous, obsessed baron (Miloš Kopecký) who may be holding a still-living Salsa Verde captive.

The steampunk elements, largely supplied by legendary animator Jan Švankmajer as the film’s prop designer, are in the castle. Keeping a mad scientist and inventor (Rudolf Hrušínský) as his minion, the baron has filled his home with ahead-of-its-time technology, from televisions to elevators to automatic sliding doors. These elements, largely drawn from the novel, attest to Verne’s visionary genius, but just as importantly, they make the castle of Baron Robert Gorc of Gorcena the kind of unpredictable, vibrantly fascinating setting that fits silly mystery comedies like a glove.

5. The City of Lost Children

In the 1990s, filmmakers Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet, both masters of the morbidly whimsical, teamed up for two singular films that made a permanent impact on the global view of French cinema. The first of those films was 1991’s “Delicatessen,” which flirted with sci-fi but was more of a dark comedy. The second, 1995’s “The City of Lost Children,” proved something any fan of Caro and Jeunet could already see coming: Their scenic design, with its predilection for dollhouse-like sets and whimsical compositions, paired perfectly with the giddy gaudiness of steampunk.

An original, underrated sci-fi movie scripted by Caro and Jeunet along with Giles Adrien, “The City of Lost Children” takes place in the kind of fully-realized fairy tale world that can carry a movie by itself. Krank (Daniel Emilfork) is a scientist who’s aging rapidly due to his inability to dream — a predicament that compels him to kidnap children and steal their dreams for himself. One day, he kidnaps Denrée (Joseph Lucien), the younger brother of circus strongman One (Ron Perlman, speaking French), and One sets out to rescue him. Caro and Jeunet lay out the action across dense, darkly-lit scenery made up of tubes, contraptions, industrial dreamscapes, and ornate metalwork. It’s a spellbinding, unrestrained cinematic vision brought to bear with full lavishness — the kind that’s becoming rare in movies.

4. Adela Has Not Had Supper Yet

Sometimes also known as “Dinner for Adele” and “Adele Hasn’t Had Her Dinner Yet,” 1978’s “Adela Has Not Had Her Supper Yet” is another mischievous steampunk triumph from Oldřich Lipský — but, instead of taking a comical approach to Jules Verne, the Czech auteur here concocts a brilliantly witty send-up of the American dime novels centered around private eye Nick Carter.

Lipský and co-screenwriter Jiří Brdečka set the action in late-19th-century Prague, where Countess Thun (Květa Fialová) has just brought over Nick Carter (Michal Dočolomanský) from the U.S. and hired him to find her missing dog. During his investigation, Carter comes across the more attention-grabbing case of Baron Ruppert von Kratzmar (Miloš Kopecký), who keeps feeding people to his carnivorous plant Adela.

With Jan Švankmajer again in tow (this time as animator), Lipský starts from the relatively simple idea of parodying old pulp thrillers, and manages to expand that enterprise into the kind of ambitious, deliriously creative, mordantly witty, slyly profound bonkers comedy that couldn’t be found anywhere else but in Czech cinema. Like in “Carpathians,” steampunk is one of the main ingredients, manifested both in the retro-technological lair of the botanist villain and in the increasingly absurd gadgets of which Nick Carter avails himself.

3. The Prestige

Christopher Nolan’s “The Prestige” is an enthralling puzzle box of a movie that keeps getting better as the brilliance of its construction dawns on you. Adapted from the eponymous 1995 novel by Christopher Priest, it’s the most literal expression of one of Nolan’s lifelong fascinations: The power of the film medium to work sheer magic before the viewer’s eyes.

A fascination with magic also fuels the obsessive rivalry of Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman) and Alfred Borden (Christian Bale), Victorian-era London illusionists who keep one-upping each other’s seemingly impossible tricks. As their showbiz feud escalates to mutual sabotage and destructive rage, they find themselves embroiled in the world of science fiction: Angier becomes convinced that Borden is creating tech-assisted tricks with the help of Nikola Tesla (David Bowie, for whose casting Nolan had no plan B), and flies out to the United States to get in on the action. But as the tricks get realer, their stakes get higher.

Nolan exhibits arguably the greatest poise of his career behind the camera, painstakingly calibrating each scene, shot, and performance so that the viewer gets properly thrown for a loop by the film’s mind-screwing twists. In fact, even the stars weren’t told how their tricks were done. The integration of steampunk elements through Tesla’s begrudging participation is nothing short of stupendous. Few other movies so thoroughly understand the spine-tingling horror of science’s ethical divestment under the logic of industry.

2. The Fabulous Baron Munchausen

There is no other movie like “The Fabulous Baron Munchausen.” Not even “Invention for Destruction,” nor any other Karel Zeman film, quite compares to it. To see Zeman’s 1962 masterpiece about a 20th century astronaut (Rudolf Jelínek) who lands on the moon and finds it already occupied by Jules Verne characters is to be bowled over at every turn, awakened to the realization that movies can do this, and this, and that, and that — yet never the wiser as to how.

Although nominally inspired by Verne’s “From the Earth to the Moon” and the literary tales of Baron Munchausen, the film is thrillingly unbound on the level of narrative, with an eagerness to jump weightlessly from idea to idea that behooves its nature as a children’s tale. On the level of image-making, meanwhile, Zeman’s work in “Munchausen” has scarcely been matched by any other filmmaker in history; he somehow harkens back to the sense of openness and possibility of early cinema, putting us in the mind of impressed fairgoers wandering into a Méliès screening in 1903.

It’s steampunk infused with the spirit of the era to which steampunk refers — sci-fi so temporally specific and rich in period texture that it becomes timeless. If the genre’s essence is retro science energized to the degree of fantasy, it doesn’t get purer than the meta-magic Zeman’s animated sequences.

1. Howl’s Moving Castle

Diana Wynne Jones’ 1986 novel “Howl’s Moving Castle” is an ebullient work of high fantasy that melds classic fairytale business with themes of personal autonomy, free will, and defiance of gender expectations. Incensed by the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, noted pacifist Hayao Miyazaki saw in Jones’ novel the potential for a hard-hitting anti-war piece. To get that theme across, he blended her imaginative mythological construction with early-20th-century technological markers, grounded and grimy and gray, the better to contrast guileless humanity with industrial devastation. The result was the best steampunk movie of all time.

Miyazaki’s most underrated masterpiece, “Howl’s Moving Castle” is a typically transcendent feat of cinematic imagination, but nowhere else in Miyazaki’s oeuvre are the moral underpinnings of his lush imagery any clearer. The titular castle alone is steampunk at its finest: a matryoshka of jaw-dropping sights, from its bulbous exterior to its endlessly surprising chambers and corridors, iconically cast against dreamy pastures. But what really seals it is the anguished precision with which Miyazaki contrasts those pastures and the war machinery that rains fire and death on them. In Miyazaki’s hands, steampunk is a conceptual extension of technology itself, able to be both enchanting and terrifying. In “Howl’s Moving Castle,” he uses the genre to make material the importance of rejecting war: The characters do, and, under the sway of the animation, so does the viewer.

Leave a Reply